Can You Speak Over the Telephone. Как вести беседу по телефону - [18]

Bye-bye, Fred.

Fred: Hello, Yuri. This is Fred.

Yuri: Hello, Freddy, how are you?

Fred: Not very well, I’m afraid.

Yuri: What’s the matter? Somebody’s ill?

Fred: No, everybody’s fine. But I’m giving up. I certainly can’t learn Russian.

Yuri: Why are you upset? I think you’re making wonderful progress.

Fred: No, I’m not. I try and try but still cannot speak it well.

Yuri: Well, learning any language takes a lot of effort and time. But don’t give up. What if I help you? I have a very good textbook only recently brought from Moscow.

Fred: Thank you, Yuri. I’m sure your help will improve things.

Yuri: See you on Monday, Freddy. Good-bye.

Fred: Thanks again, Yuri. Good-bye.

Mr Serov: Mr Budd? Good afternoon. This is Serov speaking.

Mr Budd: Hello, Mr Serov. Nice to hear you. How’s everything?

Mr Serov: Fine, thank you. You know, this Friday our Dynamo team is playing against your Red Sox.

Mr Budd: Are they really? That’s great! They are my favourite teams and I don’t know who to root for.

Mr Serov: I have two tickets. Would you like to watch the match?

Mr Budd: Sure thing. This is the only chance, and I would not miss it. And what’s your favourite sport?

Mr Serov: It’s hard to say. I like soccer all right, but I think I like tennis better.

Mr Budd: Do you play much tennis?

Mr SeroV: Yes, quite a bit. How about a game sometime?

Mr Budd: No, thanks. I am strictly a spectator.

Mr Serov: So I’m sending you the tickets for the match and hope to see you on Tuesday.

Mr Budd: Thank you, Mr Serov. I’m looking forward to seeing you. Goodbye.

Mr Serov: Good-bye.

I. Read these dialogues and reproduce them as close to the text as possible.

II. What would you say on the phone in reply to these remarks or questions?

1. I suppose, that if we weigh the “pros” and “cons” we can make a more equitable assessment of the proposal. 2. Mr Orlov, I think, made a pertinent remark during the debate. 3. If you take an overall view of things I’m sure you’ll change your opinion. 4. I like the way Peter conducted the proceedings. He kept all the discussion to the point. 5. I wouldn’t say that the speaker explicitly spelled out what he had in mind. 6. Mr Breddy is away from the office on sick leave. Is there any message? 7. I think he is making wonderful progress in English. 8. Your argument turned the scale in my favour in our dispute. 9. Why do you think, Mr Omar, the staff at your office is in constant state of flux?

III. In what situations would you say the following?

1. I don’t know which team to root for. 2. Their choice fell on me because I’m a bachelor. 3. Could you fix an alternative date for meeting? 4. I’ll leave the invitation as an open one until a little later. 5. We are anxious to make whatever arrangements are convenient to you for spending a day or two in visiting our factory. 6. Then I’ve got to think about a present. 7. This is the only outstanding question. It should be brought up again tomorrow. 8. This is a very persuasive argument. You should have mentioned it. 9. I’m terribly sorry. I can’t disturb him. He is in conference.

IV. Discuss over the phone with a friend of yours:

1. the film you have seen; 2. the book you have read; 3. the performance you have seen; 4. the conference you have attended; 5. the holiday you had in summer; 6. the invitation to a wedding party you have received; 7. your favourite sport; 8. the party you have been to.

Working in groups of two, read the two dialogues aloud.

After having an interesting tour around the Capitol, this seat of US legislation, a tourist group of foreign students surrounded their American guide, who is a member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee. They poured a forest of questions upon him.

Tourist A: We are foreigners, Sir, and do not know much either about the Congress or the State Department. Do you mind if we ask you some questions?

Guide: Of course not. Go ahead. What is it that you’d like to know?

Tourist B: Does the Congress take part in US foreign policy formulation?

Guide: Very much so. The US participation in world affairs since World War II has greatly expanded the role of the Congress in foreign policymaking.

Tourist C: We thought that this was the competence of the State Department.

Guide: This is what the foreigners usually think. The President is the central figure of American foreign policy, and the final responsibility is his.

Tourist D: And the State Secretary’s?

Guide: While the President makes the most critical decisions, he cannot possibly attend to all matters affecting international relations. The Secretary of State, the first-ranking member of the Cabinet, is at the same time the President’s principal adviser in formulating foreign policy.

Tourist A: What are the problems requiring the attention of the Secretary?

Guide: They are manifold — from maintaining country’s security to rescuing an individual American who got in serious trouble in some remoted area of the world.

Обновленное и дополненное издание бестселлера, написанного авторитетным профессором Мичиганского университета, – живое и увлекательное введение в мир литературы с его символикой, темами и контекстами – дает ключ к более глубокому пониманию художественных произведений и позволяет сделать повседневное чтение более полезным и приятным. «Одно из центральных положений моей книги состоит в том, что существует некая всеобщая система образности, что сила образов и символов заключается в повторениях и переосмыслениях.

Монография, посвященная специфическому и малоизученному пласту американской неформальной лексики, – сленгу военнослужащих армии США. Написанная простым и понятным языком, работа может быть интересна не только лингвистам и военным, но и простым читателям.

Ноам Хомский, по мнению газеты Нью-Йорк Таймс, самый значимый интеллектуал из ныне живущих. В России он тоже популярный автор, один из властителей дум. Боб Блэк в этой книге рассматривает Хомского как лингвиста, который многим представляется светилом, и как общественного деятеля, которого многие считают анархистом. Пришла пора разобраться в научной работе и идеях Хомского, если мы хотим считаться его единомышленниками. И нужно быть готовыми ко всесторонней оценке его наследия – без церемоний.

Институт литературы в России начал складываться в царствование Елизаветы Петровны (1741–1761). Его становление было тесно связано с практиками придворного патронажа – расцвет словесности считался важным признаком процветающего монархического государства. Развивая работы литературоведов, изучавших связи русской словесности XVIII века и государственности, К. Осповат ставит теоретический вопрос о взаимодействии между поэтикой и политикой, между литературной формой, писательской деятельностью и абсолютистской моделью общества.

«Как начинался язык» предлагает читателю оригинальную, развернутую историю языка как человеческого изобретения — от возникновения нашего вида до появления более 7000 современных языков. Автор оспаривает популярную теорию Ноама Хомского о врожденном языковом инстинкте у представителей нашего вида. По мнению Эверетта, исторически речь развивалась постепенно в процессе коммуникации. Книга рассказывает о языке с позиции междисциплинарного подхода, с одной стороны, уделяя большое внимание взаимовлиянию языка и культуры, а с другой — особенностям мозга, позволившим человеку заговорить. Хотя охотники за окаменелостями и лингвисты приблизили нас к пониманию, как появился язык, открытия Эверетта перевернули современный лингвистический мир, прогремев далеко за пределами академических кругов.

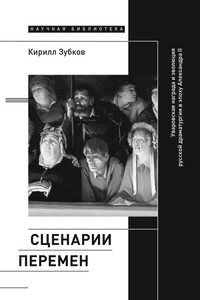

В 1856 году известный археолог и историк Алексей Сергеевич Уваров обратился к членам Академии наук с необычным предложением: он хотел почтить память своего недавно скончавшегося отца, бывшего министра народного просвещения С. С. Уварова, учредив специальную премию, которая должна была ежегодно вручаться от имени Академии за лучшую пьесу и за лучшее исследование по истории. Немалые средства, полагавшиеся победителям, Уваров обещал выделять сам. Академики с благодарностью приняли предложение мецената и учредили первую в России литературную премию.