Стихи - [22]

From the far tower where Milton's Platonist

Sat late, or Shelley's visionary prince:

The lonely light that Samuel Palmer engraved,

An image of mysterious wisdom won by toil;

And now he seeks in book or manuscript

What he shall never find.

Aherne. Why should not you

Who know it all ring at his door, and speak

Just truth enough to show that his whole life

Will scarcely find for him a broken crust

Of all those truths that are your daily bread;

And when you have spoken take the roads again?

Robartes. He wrote of me in that extravagant style

He had learnt from Pater, and to round his tale

Said I was dead; and dead I choose to be.

Aherne. Sing me the changes of the moon once more;

True song, though speech: "mine author sung it me."

Robartes. Twenty-and-eight the phases of the moon,

The full and the moon's dark and all the crescents,

Twenty-and-eight, and yet but six-and-twenty

The cradles that a man must needs be rocked in:

For thereТs no human life at the full or the dark.

From the first crescent to the half, the dream

But summons to adventure and the man

Is always happy like a bird or a beast;

But while the moon is rounding towards the full

He follows whatever whim's most difficult

Among whims not impossible, and though scarred,

As with the cat-o'-nine-tails of the mind,

His body moulded from within his body

Grows comelier. Eleven pass, and then

Athene takes Achilles by the hair,

Hector is in the dust, Nietzsche is born,

Because the hero's crescent is the twelfth.

And yet, twice born, twice buried, grow he must,

Before the full moon, helpless as a worm.

The thirteenth moon but sets the soul at war

In its own being, and when that war's begun

There is no muscle in the arm; and after,

Under the frenzy of the fourteenth moon,

The soul begins to tremble into stillness,

To die into the labyrinth of itself!

Aherne. Sing out the song; sing to the end, and sing

The strange reward of all that discipline.

Robartes. All thought becomes an image and the soul

Becomes a body: that body and that soul

Too perfect at the full to lie in a cradle,

Too lonely for the traffic of the world:

Body and soul cast out and cast away

Beyond the visible world.

Aherne. All dreams of the soul

End in a beautiful man's or woman's body.

Robartes. Have you not always known it?

Aherne. The song will have it

That those that we have loved got their long fingers

From death, and wounds, or on Sinai's top,

Or from some bloody whip in their own hands.

They ran from cradle to cradle till at last

Their beauty dropped out of the loneliness

Of body and soul.

Robartes. The lover's heart knows that.

Aherne. It must be that the terror in their eyes

Is memory or foreknowledge of the hour

When all is fed with light and heaven is bare.

Robartes. When the moonТs full those creatures of the full

Are met on the waste hills by countrymen

Who shudder and hurry by: body and soul

Estranged amid the strangeness of themselves,

Caught up in contemplation, the mind's eye

Fixed upon images that once were thought;

For separate, perfect, and immovable

Images can break the solitude

Of lovely, satisfied, indifferent eyes.

And thereupon with aged, high-pitched voice

Aherne laughed, thinking of the man within,

His sleepless candle and laborious pen.

Robartes. And after that the crumbling of the moon.

The soul remembering its loneliness

Shudders in many cradles; all is changed,

It would be the world's servant, and as it serves,

Choosing whatever task's most difficult

Among tasks not impossible, it takes

Upon the body and upon the soul

The coarseness of the drudge.

Aherne. Before the full

It sought itself and afterwards the world.

Robartes. Because you are forgotten, half out of life,

And never wrote a book, your thought is clear.

Reformer, merchant, statesman, learned man,

Dutiful husband, honest wife by turn,

Cradle upon cradle, and all in flight and all

Deformed because there is no deformity

But saves us from a dream.

Aherne. And what of those

That the last servile crescent has set free?

Robartes. Because all dark, like those that are all light,

They are cast beyond the verge, and in a cloud,

Crying to one another like the bats;

And having no desire they cannot tell

WhatТs good or bad, or what it is to triumph

At the perfection of oneТs own obedience;

And yet they speak what's blown into the mind;

Deformed beyond deformity, unformed,

Insipid as the dough before it is baked,

They change their bodies at a word.

Aherne. And then?

Rohartes. When all the dough has been so kneaded up

That it can take what form cook Nature fancies,

The first thin crescent is wheeled round once more.

Aherne. But the escape; the song's not finished yet.

Robartes. Hunchback and Saint and Fool are the last crescents.

The burning bow that once could shoot an arrow

Out of the up and down, the wagon-wheel

Of beauty's cruelty and wisdom's chatter-

Out of that raving tide-is drawn betwixt

Deformity of body and of mind.

Aherne. Were not our beds far off I'd ring the bell,

Stand under the rough roof-timbers of the hall

Beside the castle door, where all is stark

Austerity, a place set out for wisdom

That he will never find; I'd play a part;

В книге рассказывается история главного героя, который сталкивается с различными проблемами и препятствиями на протяжении всего своего путешествия. По пути он встречает множество второстепенных персонажей, которые играют важные роли в истории. Благодаря опыту главного героя книга исследует такие темы, как любовь, потеря, надежда и стойкость. По мере того, как главный герой преодолевает свои трудности, он усваивает ценные уроки жизни и растет как личность.

Уильям Батлер Йейтс (1865–1939) — классик ирландской и английской литературы ХХ века. Впервые выходящий на русском языке том прозы "Кельтские сумерки" включает в себя самое значительное, написанное выдающимся писателем. Издание снабжено подробным культурологическим комментарием и фундаментальной статьей Вадима Михайлина, исследователя современной английской литературы, переводчика и комментатора четырехтомного "Александрийского квартета" Лоренса Даррелла (ИНАПРЕСС 1996 — 97). "Кельтские сумерки" не только собрание увлекательной прозы, но и путеводитель по ирландской истории и мифологии, которые вдохновляли У.

Пьеса повествует о смерти одного из главных героев ирландского эпоса. Сюжет подан, как представление внутри представления. Действие, разворачивающееся в эпоху героев, оказывается обрамлено двумя сценами из современности: стариком, выходящим на сцену в самом начале и дающим наставления по работе со зрительным залом, и уличной труппой из двух музыкантов и певицы, которая воспевает героев ирландского прошлого и сравнивает их с людьми этого, дряхлого века. Пьеса, завершающая цикл посвящённый Кухулину, пронизана тоской по мифологическому прошлому, жившему по другим законам, но бывшему прекрасным не в пример настоящему.

Уильям Батлер Йейтс (1865–1939) – великий поэт, прозаик и драматург, лауреат Нобелевской премии, отец английского модернизма и его оппонент – называл свое творчество «трагическим», видя его основой «конфликт» и «войну противоположностей», «водоворот горечи» или «жизнь». Пьесы Йейтса зачастую напоминают драмы Блока и Гумилева. Но для русских символистов миф и история были, скорее, материалом для переосмысления и художественной игры, а для Йейтса – вечно живым источником изначального жизненного трагизма.

Эта пьеса погружает нас в атмосферу ирландской мистики. Капитан пиратского корабля Форгэл обладает волшебной арфой, способной погружать людей в грезы и заставлять видеть мир по-другому. Матросы довольны своим капитаном до тех пор, пока всё происходит в соответствии с обычными пиратскими чаяниями – грабёж, женщины и тому подобное. Но Форгэл преследует другие цели. Он хочет найти вечную, высшую, мистическую любовь, которой он не видел на земле. Этот центральный образ, не то одержимого, не то гения, возвышающегося над людьми, пугающего их, но ведущего за собой – оставляет широкое пространство для толкования и заставляет переосмыслить некоторые вещи.

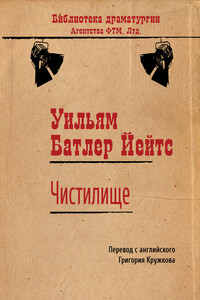

Старик и юноша останавливаются у разрушенного дома. Выясняется, что это отец и сын, а дом когда-то принадлежал матери старика, которая происходила из добропорядочной семьи. Она умерла при родах, а муж её, негодяй и пьяница, был убит, причём убит своим сыном, предстающим перед нами уже стариком. Его мучают воспоминания, образ матери возникает в доме. Всем этим он делится с юношей и поначалу не замечает, как тот пытается убежать с их деньгами. Но между ними начинается драка и Старик убивает своего сына тем же ножом, которым некогда убил и своего отца, завершая некий круг мучающих его воспоминаний и пресекая в сыне то, что было страшного в его отце.