Периферийный авторитаризм. Как и куда пришла Россия - [61]

– one leader” principle not only feasible but rather an inevitable achievement. By the time this book is published elections at almost every level have come to produce results that are 95% predictable, while the remaining 5% could be managed by other means or simply neglected. On the other hand, big private business not linked to big government survives, if it does, as a poor relic of the so-called “oligarchy” of the 1990s, and the last thing it wants to be thought of is its having any political ambitions.

As a result, what we are witnessing now in Russia is a consolidated, fully-fledgedautocracywith an indisputable leader presiding over privileged bureaucracy and a very large strata of public and semi-public workers, as well as straight dependents of the state, who rely on the government for their income and protection against all sorts of menace, both real and imaginary.

The reasons for that are plentiful, but one important factor, which is stressed in this book as being of utmost importance, is that contemporary Russia that emerged on the ruins of a former communist superpower is a peripheral and subordinated part of the global capitalist civilization, of its economy, technologies and politics.

Russia’s role in the global economy is limited to that of a supplier of hydrocarbons (and a small portion of other primary products) to more advanced and wealthy nations, with little chance of breaking the vicious circle oflow position, poor efficiency and low status. The result is an almost complete absence of sovereign business class, self-conscious and independent from government bureaucracy, which would be eager to integrate itself into global business aristocracy. Hence little motivation can be expected in the Russian political class to change domestic political and business rules in order to gain competitive power and international advantages.

The drive towards fully-fledged autocracy has been made easier by the weak political position of the country and its low economic status. Lack of powerful economic and political leverage intensifies Russia’s frictions with global political leaders, who tend to impose their will on the rest of the world. The resulting frustration nourishes authoritarian political trends and the forces promoting them while undermining the position of those advocating an open and free political system.

Moreover, the psychological heritage of a former superpower’s past glory and fancy ideas of a global mission come into unbearable contradiction with Russia’s dependent and subordinate position within the global hierarchy. That makes the Russian elite resent the rules being imposed on it by the established world leaders as well as those who are trying to do it. Putin’s anti-Western mood stems not so much from his personal views and tastes, but rather from the general sense of discomfort of the entire Russian establishment, aspiring to join the upper ranks of the world elite but failing to produce solid good reason to demand that.

The recent crisis in Russia-Ukraine and Russia-West relations should be analyzed with a broader view of the changing situation in Russia. In fact, it is only a piece of a bigger puzzle, an outer extension of deep divisions and frustrations tormenting the collective mind of the Russian political class.

It is true that major decisions in the Russian government system are made at the very top. Nevertheless, the top relies on reports from a broader range of administrators and functionaries who form the mood and presuppose the range of possible decisions. Political class at large is not a passive recipient of decisions made at the top – rather it determines their direction and range.

An acute and menacing crisis in Russia’s relations with the West resulting from Putin’s rejection of rules of behavior which are considered by the West to be universal and obligatory, is to a large degree his personal choice reflecting his personal vision. Nevertheless, the decision was not completely personal and free – it came in the logic of consolidating the autocratic government system which made systemic break with the West inevitable. Moreover, the need for consolidation of the system came out of its obvious inability to solve the problems Russia faces.

The control of the very top over the entire system, its governability and sense of stability have been undermined by a sharp reduction of growth rates and mounting difficulties in extracting dictatorial rent from the economy to be distributed among the privileged bureaucracy and thus uphold the autocratic rule. That produced the need to find new instruments to consolidate the system like more official indoctrination and control over media, accentuating real and imaginary dangers from external and internal “enemies”, fostering the feeling of being victimized by a hostile world.

Hence, the situation could not be reversed easily by a single decision, even if Putin were prepared to make it. To turn the tide back, systemic changes in the mindset and world vision of the Russian political class are a necessary condition. This is a fundamentally difficult task that would take years to solve, but there is no other way to achieve a lasting settlement. Attempts to solve the issue by sanctions and private deals with Putin will be short-lived and ultimately fruitless. The only practical way to prevent Russia from fundamentally isolating itself from the West is to make it choose a difficult and painful road of converging with the mainstream of global capitalism and adapting to its realities and to wage an honest dialogue with the Russian political class at large.

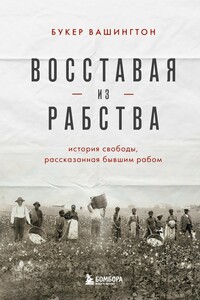

С чего началась борьба темнокожих рабов в Америке за право быть свободными и называть себя людьми? Как она превратилась в BLM-движение? Через что пришлось пройти на пути из трюмов невольничьих кораблей на трибуны Парламента? Американский классик, писатель, политик, просветитель и бывший раб Букер Т. Вашингтон рассказывает на страницах книги историю первых дней борьбы темнокожих за свои права. О том, как погибали невольники в трюмах кораблей, о жестоких пытках, невероятных побегах и создании системы «Подземная железная дорога», благодаря которой сотни рабов сумели сбежать от своих хозяев. В формате PDF A4 сохранен издательский макет книги.

В книге рассказывается история главного героя, который сталкивается с различными проблемами и препятствиями на протяжении всего своего путешествия. По пути он встречает множество второстепенных персонажей, которые играют важные роли в истории. Благодаря опыту главного героя книга исследует такие темы, как любовь, потеря, надежда и стойкость. По мере того, как главный герой преодолевает свои трудности, он усваивает ценные уроки жизни и растет как личность.

В книге рассказывается история главного героя, который сталкивается с различными проблемами и препятствиями на протяжении всего своего путешествия. По пути он встречает множество второстепенных персонажей, которые играют важные роли в истории. Благодаря опыту главного героя книга исследует такие темы, как любовь, потеря, надежда и стойкость. По мере того, как главный герой преодолевает свои трудности, он усваивает ценные уроки жизни и растет как личность.

В книге рассказывается история главного героя, который сталкивается с различными проблемами и препятствиями на протяжении всего своего путешествия. По пути он встречает множество второстепенных персонажей, которые играют важные роли в истории. Благодаря опыту главного героя книга исследует такие темы, как любовь, потеря, надежда и стойкость. По мере того, как главный герой преодолевает свои трудности, он усваивает ценные уроки жизни и растет как личность.

В книге рассказывается история главного героя, который сталкивается с различными проблемами и препятствиями на протяжении всего своего путешествия. По пути он встречает множество второстепенных персонажей, которые играют важные роли в истории. Благодаря опыту главного героя книга исследует такие темы, как любовь, потеря, надежда и стойкость. По мере того, как главный герой преодолевает свои трудности, он усваивает ценные уроки жизни и растет как личность.

В книге рассказывается история главного героя, который сталкивается с различными проблемами и препятствиями на протяжении всего своего путешествия. По пути он встречает множество второстепенных персонажей, которые играют важные роли в истории. Благодаря опыту главного героя книга исследует такие темы, как любовь, потеря, надежда и стойкость. По мере того, как главный герой преодолевает свои трудности, он усваивает ценные уроки жизни и растет как личность.