Англо-русский учебный словарь 1984 - [3]

The user.

Coverage (lexis).

The language.

Illustration.

Layout.

Order within an entry.

Translation of headwords.

Grammatical indications.

Stylistic and Field labels.

Indicators of meaning.

NOTES FOR USERS

Order of the entries.

Pronunciation.

Use of the tilde.

Use of the hyphen, and of the hyphen plus vertical stroke.

Use of brackets.

Indicating alternatives: the diagonal stroke, the comma, and "or".

Grammar: treatment of nouns.

Grammar: treatment of verbs.

Verbs of motion with two imperfectives.

The translation of "it".

INTRODUCTION

THE USER

This dictionary is primarily a practical one for the student whose approach to the Russian language will be through English, irrespective of whether he lives in Britain, North America or elsewhere. The vocabulary comprises the words which the average educated man might want to use in speaking or writing Russian, including the simple technical terms in common use.

The criterion for method has been ease in use, or, in the words of James Murray, "eloquence to the eye". Clutter in the text reduces clarity and adds to eyestrain. For this reason cross-references are avoided as far as possible. Much use is made of clearly marked divisions and the dictionary is well provided with indications of style and shades of meaning, and with occasional grammatical notes and cautions. The student should thus be able to find what he wants easily and quickly, without constant recourse either to his grammar or to a Russian-English dictionary.

There is a wealth of illustrative phrases, couched in the language of "everyday** and these should help to give the student the feel of spoken Russian.

COVERAGE (LEXIS)

The nature of the dictionary has determined the vocabulary. Very full treatment has been given to the few basic words which figure so largely in our daily use—do, get, give, go, make, put, way, etc., as also to prepositions. Special attention is paid to verbs in combination with prepositions or adverbial particles, which are usually translated by Russian verbal prefixes. These are of the first importance to the student. All the commoner senses of the selected English headwords have been covered, but not necessarily rare ones. Thus for instance when a verb is nearly always used in the transitive form, although the intransitive form exists (or vice versa), the rare usage may be ignored.

To 'save space, abstract nouns and adverbs derived directly from adjectives are not given, e.g. tender adj нежный is given, but not tenderness n нежность, nor tenderly adv нежно.

In groups of cognate words, such as biological, biologist, biology, one or more of the terms may be omitted. Similarly English words which are translated by direct transliteration into Russian are often omitted, e.g. morgue морг, or nymph нимфа. In such cases it will be easy for the student to form or find these for himself.

THE LANGUAGE

Emphasis has been given to the spoken language—both everyday colloquial uses and more specialized uses, e.g. the' language of the committee man. Many of the examples are given in the second person singular indicating exchanges between friends of the. same age, or colleagues of the same rank, or members of a family. A strong distinction is made between colloquial expressions and slang, the latter being included only if it is well established, partly because it can date so quickly, partly because it is hard to appreciate its exact tone in a foreign language. Translations are as far as possible stylistically matched. Where there is no true equivalent of an English expression such as ghost writer, it has seemed better to omit the term rather than to offer explanations or cumbrous circumlocutions, which the student could equally well form for himself if need arose.

ILLUSTRATION

Translation by single words seldom enables the student to use these words in a living context. The illustrations are designed to provide such a context. They also show the difference between the two languages in construction and grammar where rules apply. For example, translation of the English predicative adjective does not always in Russian follow directly from the attributive form, e.g. unconnected sentences несвязные фразы, but the two events are quite unconnected эти два события никак не связаны между собой.

Illustrations also serve to familiarize the student with Russian word combinations and word order, and with the typical flow and rhythm of the Russian sentence, none of which can be deduced a priori. Though word order in both languages is flexible, varying according to emphasis, nevertheless there are standard patterns of order where the two languages differ, e.g. she walked in her sleep last night сегодня [NB] ночью он ходйла во сне. Again the invariable English cadence is supply and demand, but the Russians prefer спрос и предложение.

LAYOUT

All English words and phrases are printed in bold type. Indicators (of style, meaning, etc.) are printed in italics. Long entries are divided; each division is numbered, begins on a new line and is inset. But short entries which can be taken in at a glance, may contain no divisions, even when these would be justified semantically.

Так как же рождаются слова? И как создать такое слово, которое бы обрело свою собственную и, возможно, очень долгую жизнь, чтобы оставить свой след в истории нашего языка? На этот вопрос читатель найдёт ответ, если отправится в настоящее исследовательское путешествие по бескрайнему морю русских слов, которое наглядно покажет, как наши предки разными способами сложения старых слов и их образов создавали новые слова русского языка, древнее и богаче которого нет на земле.

Набоков ставит себе задачу отображения того, что по природе своей не может быть адекватно отражено, «выразить тайны иррационального в рациональных словах». Сам стиль его, необыкновенно подвижный и синтаксически сложный, кажется лишь способом приблизиться к этому неизведанному миру, найти ему словесное соответствие. «Не это, не это, а что-то за этим. Определение всегда есть предел, а я домогаюсь далей, я ищу за рогатками (слов, чувств, мира) бесконечность, где сходится все, все». «Я-то убежден, что нас ждут необыкновенные сюрпризы.

Содержание этой книги напоминает игру с огнём. По крайней мере, с обывательской точки зрения это, скорее всего, будет выглядеть так, потому что многое из того, о чём вы узнаете, прилично выделяется на фоне принятого и самого простого языкового подхода к разделению на «правильное» и «неправильное». Эта книга не для борцов за чистоту языка и тем более не для граммар-наци. Потому что и те, и другие так или иначе подвержены вспышкам языкового высокомерия. Я убеждена, что любовь к языку кроется не в искреннем желании бороться с ошибками.

Литературная деятельность Владимира Набокова продолжалась свыше полувека на трех языках и двух континентах. В книге исследователя и переводчика Набокова Андрея Бабикова на основе обширного архивного материала рассматриваются все основные составляющие многообразного литературного багажа писателя в их неразрывной связи: поэзия, театр и кинематограф, русская и английская проза, мемуары, автоперевод, лекции, критические статьи и рецензии, эпистолярий. Значительное внимание в «Прочтении Набокова» уделено таким малоизученным сторонам набоковской творческой биографии как его эмигрантское и американское окружение, участие в литературных объединениях, подготовка рукописей к печати и вопросы текстологии, поздние стилистические новшества, начальные редакции и последующие трансформации замыслов «Камеры обскура», «Дара» и «Лолиты».

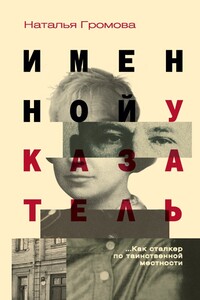

Наталья Громова – прозаик, историк литературы 1920-х – 1950-х гг. Автор документальных книг “Узел. Поэты. Дружбы. Разрывы”, “Распад. Судьба советского критика в 40-е – 50-е”, “Ключ. Последняя Москва”, “Ольга Берггольц: Смерти не было и нет” и др. В книге “Именной указатель” собраны и захватывающие архивные расследования, и личные воспоминания, и записи разговоров. Наталья Громова выясняет, кто же такая чекистка в очерке Марины Цветаевой “Дом у старого Пимена” и где находился дом Добровых, в котором до ареста жил Даниил Андреев; рассказывает о драматурге Александре Володине, о таинственном итальянском журналисте Малапарте и его знакомстве с Михаилом Булгаковым; вспоминает, как в “Советской энциклопедии” создавался уникальный словарь русских писателей XIX – начала XX века, “не разрешенных циркулярно, но и не запрещенных вполне”.

В книге рассказывается история главного героя, который сталкивается с различными проблемами и препятствиями на протяжении всего своего путешествия. По пути он встречает множество второстепенных персонажей, которые играют важные роли в истории. Благодаря опыту главного героя книга исследует такие темы, как любовь, потеря, надежда и стойкость. По мере того, как главный герой преодолевает свои трудности, он усваивает ценные уроки жизни и растет как личность.