The Catalyst Killing - [32]

I took the liberty of reminding Christian Magnus Eggen that he had not always been a law-abiding citizen. He snorted in contempt and replied that he had never broken the law of the day – what happened in 1945 was that the law was amended with retrospective effect. He would never have believed that one could be punished in Norway for nothing more than being a member of a political party. And in order to avoid any chance of experiencing something similar again, he had not been politically active since. After all, he remarked snidely, it was impossible to know whether the socialists might suddenly decide tomorrow to ban any of the right-wing parties with retrospective effect.

We had not got off to a good start. And I did not make things any better by allowing myself to be provoked into asking if he denied any knowledge of the persecution of the Jews during the war.

‘What persecution of the Jews?’ he challenged, looking me straight in the eye.

‘The Holocaust – the genocide of six million Jews, organized by Hitler’s Germany and supported by Quisling’s NS,’ I replied, also with a certain antagonism.

He rolled his eyes.

‘So even senior civil servants have allowed themselves to be brainwashed by the lies of their parents. What you call the Holocaust is an illusion based on exaggerated lies. A few Jewish criminals were executed, as more criminals and antisocial elements should be. But the Jews themselves are primarily to blame for their persecution in Germany. After all, they chose to stay there rather than give up their businesses, despite all the well-intentioned warnings. It was never a case of industrial genocide. I went there myself and saw the so-called annihilation camps – and they simply did not have the capacity to do anything like that. There are no documents signed by Hitler or members of his government to authorize anything of the sort. Some members of the German army may, at the height of the war, have overstepped their orders to tackle antisocial elements, but there was never an organized genocide.’

I stared at the man on the sofa with horrified fascination. His smile was bitter.

‘Next you’ll be saying that you believe the lie that Norway was occupied by the Germans. There was no German occupation; it was a rescue operation to save Norway from becoming part of the British Empire. There is evidence that the British had already started their invasion and had laid out mines in Norwegian territorial waters when the Germans arrived. And when the government and king decided to leave the country on 7 June 1940 rather than stay here to serve their people, Norway was no longer at war. In 1945, I and many other law-abiding citizens were convicted of being war criminals in a country that had not been at war, because we had used our given right to express our political views while obeying the laws that were current at the time.’

It was not easy to argue with the increasingly passionate Christian Magnus Eggen, partly because he was agitated and talking so fast, but also because I was at a bit of a loss and my knowledge of wartime Norway was obviously inferior to his. So I simply said that his understanding of the war was obviously very different from my own – and that given in Norwegian history books – but that that was not why I had come to see him. He gave an impatient nod, and then calmed down a bit and waited.

When we finally got down to business, Christian Magnus Eggen’s story was more or less the same in content as Frans Heidenberg’s, despite their outward differences. Marie Morgenstierne was just a name that he had read in the week’s newspapers. But he had first heard of Falko Reinhardt as a prominent young communist. When he then received a letter from him, with some questions about his experiences during the war, he had not wanted to waste ‘five minutes and a stamp’ on the answers. He had instead said exactly what he thought when Falko Reinhardt subsequently called him. He had thus spoken to Falko Reinhardt on the telephone for a couple of minutes, but had never seen the man.

As it was so long ago, Christian Magnus Eggen could no longer say what he had been doing on the night that Falko Reinhardt disappeared, but he could guarantee that he had not been in Valdres. He had been at home alone on the evening that Marie Morgenstierne was shot.

He did not, however, understand why he had to answer these questions about two people he had never met or had any significant contact with. He had no kind of motive whatsoever, and there was absolutely nothing to link him to the scene of the crime. And in any case, he added with a sarcastic smile, no one knew for certain that one of them had been the victim of a criminal act.

I was starting to feel very angry. I said that some information had come to light that could indicate that he had been a member of a Nazi network during the war.

Christian Magnus Eggen snorted with even more contempt than before. He had done nothing more than be involved with the lawful activities of a political party that was legal at the time, and was engaged in the fight to save Norway from the threat of communism. He had been a member of the NS and done business with the Germans, but had not played a central role or been part of any network. And in later years he had minded his own business, paid his tax and not been politically active in any way. In addition, his right to vote had been suspended for a decade after the war due to his political affiliations, and he had since chosen not to use it in protest. The Conservatives and Labour were all the same to him. He had, however, continued to have contact with Frans Heidenberg and a few other old friends, which, as far as he was aware, was still not illegal.

Убит бывший лидер норвежского Сопротивления и бывший член кабинета министров Харальд Олесен. Его тело обнаружено в запертой квартире, следов взлома нет, орудие убийства отсутствует. На звук выстрела к двери Олесена сбежались все соседи, но никого не увидели. Инспектор уголовного розыска Колбьёрн Кристиансен считает, что убийство, скорее всего, совершил кто-то из них. Более того, он полагает, что их показания лживы.

A gripping, evocative, and ingenious mystery which pays homage to Agatha Christie, Satellite People is the second Norwegian mystery in Hans Olav Lahlum's series. Oslo, 1969: When a wealthy man collapses and dies during a dinner party, Norwegian Police Inspector Kolbjorn Kristiansen, known as K2, is left shaken. For the victim, Magdalon Schelderup, a multimillionaire businessman and former resistance fighter, had contacted him only the day before, fearing for his life. It soon becomes clear that every one of Schelderup's 10 dinner guests is a suspect in the case.

Oslo, 1968: ambitious young detective Inspector Kolbjorn Kristiansen is called to an apartment block, where a man has been found murdered. The victim, Harald Olesen, was a legendary hero of the Resistance during the Nazi occupation, and at first it is difficult to imagine who could have wanted him dead. But as Detective Inspector Kolbjorn Kristiansen (known as K2) begins to investigate, it seems clear that the murderer could only be one of Olesen's fellow tenants in the building. Soon, with the help of Patricia – a brilliant young woman confined to a wheelchair following a terrible accident – K2 will begin to untangle the web of lies surrounding Olesen's neighbors; each of whom, it seems, had their own reasons for wanting Olesen dead.

From the international bestselling author, Hans Olav Lahlum, comes Chameleon People, the fourth murder mystery in the K2 and Patricia series.1972. On a cold March morning the weekend peace is broken when a frantic young cyclist rings on Inspector Kolbjorn 'K2' Kristiansen's doorbell, desperate to speak to the detective.Compelled to help, K2 lets the boy inside, only to discover that he is being pursued by K2's colleagues in the Oslo police. A bloody knife is quickly found in the young man's pocket: a knife that matches the stab wounds of a politician murdered just a few streets away.The evidence seems clear-cut, and the arrest couldn't be easier.

Тупик. Стена. Старый кирпич, обрывки паутины. А присмотреться — вроде следы вокруг. Может, отхожее место здесь, в глухом углу? Так нет, все чисто. Кто же сюда наведывается и зачем? И что охраняет тут охрана? Да вот эту стену и охраняет. Она, как выяснилось, с секретом: время от времени отъезжает в сторону. За ней цех. А в цеху производят под видом лекарства дурь. Полковник Кожемякин все это выведал. Но надо проникнуть внутрь и схватить за руку отравителей, наживающихся на здоровье собственного народа. А это будет потруднее…

«Посмотреть в послезавтра» – остросюжетный роман-триллер Надежды Молчадской, главная изюминка которого – атмосфера таинственности и нарастающая интрига.Девушка по имени Венера впадает в кому при загадочных обстоятельствах. Спецслужбы переправляют ее из закрытого городка Нигдельск в Москву в спецклинику, где известный ученый пытается понять, что явилось причиной ее состояния. Его исследования приводят к неожиданным результатам: он обнаруживает, что их связывает тайна из его прошлого.

«ИСКАТЕЛЬ» — советский и российский литературный альманах. Издаётся с 1961 года. Публикует фантастические, приключенческие, детективные, военно-патриотические произведения, научно-популярные очерки и статьи. В 1961–1996 годах — литературное приложение к журналу «Вокруг света», с 1996 года — независимое издание.В 1961–1996 годах выходил шесть раз в год, в 1997–2002 годах — ежемесячно; с 2003 года выходит непериодически.Содержание:Анатолий Королев ПОЛИЦЕЙСКИЙ (повесть)Олег Быстров УКРАДИ МОЮ ЖИЗНЬ (окончание) (повесть)Владимир Лебедев ГОСТИ ИЗ НИОТКУДА.

«ИСКАТЕЛЬ» — советский и российский литературный альманах. Издается с 1961 года. Публикует фантастические, приключенческие, детективные, военно-патриотические произведения, научно-популярные очерки и статьи. В 1961–1996 годах — литературное приложение к журналу «Вокруг света», с 1996 года — независимое издание.В 1961–1996 годах выходил шесть раз в год, в 1997–2002 годах — ежемесячно; с 2003 года выходит непериодически.Содержание:Олег Быстров УКРАДИ МОЮ ЖИЗНЬ (повесть);Петр Любестовский КЛЕТКА ДЛЯ НУТРИИ (повесть)

Наталья Земскова — журналист, театральный критик. В 2010 г. в издательстве «Астрель» (Санкт-Петербург) вышел её роман «Детородный возраст», который выдержал несколько переизданий. Остросюжетный роман «Город на Стиксе» — вторая книга писательницы. Молодая героиня, мечтает выйти замуж и уехать из забитого новостройками областного центра. Но вот у неё на глазах оживают тайны и легенды большого губернского города в центре России, судьбы талантливых людей, живущих рядом с нею. Роман «Город на Стиксе» — о выборе художника — провинция или столица? О том, чем рано или поздно приходится расплачиваться современному человеку, не верящему ни в Бога, ни в черта, а только в свой дар — за каждый неверный шаг.

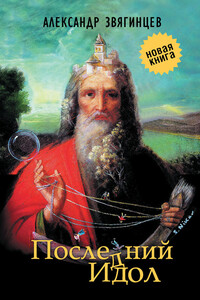

В сборник «Последний идол» вошли произведения Александра Звягинцева разных лет и разных жанров. Они объединены общей темой исторической памяти и личной ответственности человека в схватке со злом, которое порой предстает в самых неожиданных обличиях. Публикуются рассказы из циклов о делах следователей Багринцева и Северина, прокуроров Ольгина и Шип — уже известных читателям по сборнику Звягинцева «Кто-то из вас должен умереть!» (2012). Впервые увидит свет пьеса «Последний идол», а также цикл очерков писателя о событиях вокруг значительных фигур общественной и политической жизни России XIX–XX веков — от Петра Столыпина до Солженицына, от Александра Керенского до Льва Шейнина.