Еврейские Евангелия. История еврейского Христа [заметки]

1

Paula Fredriksen, "Mandatory Retirement: Ideas in the Study of Christian Origins Whose Time Has Come to Go/' in Israel's

God and Rebecca's Children: Christology and Community in Early Judaism and Christianity: Essays in Honor of Larry W.

Hurtado and Alan F. Segal, ed. David B. Capes et al. (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2007), 25.

2

I will be developing this idea further in a forthcoming book, entitled How the Jews Got Religion (New York: Fordham University

Press, 2013).

3

Shaye J. D. Cohen, "The Significance of Yavneh: Pharisees, Rabbis, and the End of Jewish Sectarianism," Hebrew Union College

Annual 55 (1984): 27-53.

4

For one of the best historical descriptions of this process, see R. P. C. Hanson, The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God: The Arian Controversy 318-381 AD (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1988).

5

Robert L. Wilken, John Chrysostom and the Jews: Rhetoric and Reality in the Late 4th Century (Berkeley: University of California

Press, 1983).

6

Jerome, Correspondence, ed. Isidorus Hilberg, Corpus Scrip torum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum (Vienna: Verlag der Osterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1996), 55:381-82 (my translation).

7

The era of the "Aryan Jesus" is over, thankfully. Susannah Heschel, The Aryan Jesus: Christian Theologians and the Bible in Nazi Germany (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008).

8

Craig C. Hill, "The Jerusalem Church," in Jewish Christianity Reconsidered: Rethinking Ancient Groups and Texts, ed. Matt Jackson—McCabe (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2007), 50.

9

Joseph Fitzmyer, The One Who Is to Come (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2007), 9.1 have drawn much on Fitzmyer's exposition for this section.

10

To be sure, the person of the king has a sacralized quality, and moreover, as we see in the case of Saul himself, even an ecstatic or prophetic measure. (Is Saul among the prophets?)

11

For discussion, see A. Y. Collins and J. J. Collins, King and Messiah as Son of God: Divine, Human, and Angelic Messianic Figures in Biblical and Related Literature (Grand Rapids, MI: W. B.

Eerdmans, 2008), 16-19.

12

For a good survey, see Delbert Royce Burkett, The Son of Man Debate: A History and Evaluation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

13

For the literature supporting this view, see John J. Collins, "The Son of Man and the Saints of the Most High in the Book of Daniel," Journal of Biblical Literature 93, no. 1 (March 1974): 50n2. In his view, the one like a son of man is Michael. He represents Israel, as its heavenly "prince," quite explicitly in chapters 10-12. Collins, accordingly, disagrees with me, thinking that the interpretation in Daniel 7 does not demote him at all. In both chapters 7 and 10-12, for Collins, reality is depicted on two levels. I would only remark that Collins's interpretation is by no means impossible, but I nonetheless prefer the one I have offered in the text for reasons made most clear in my article in the Harvard Theological Review, as well as on grounds of relative simplicity.

14

Louis Francis Hartman and Alexander A. Di Leila, The Book of Daniel, trans. Louis Francis Hartman, The Anchor Bible (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1978), 101. They themselves list Exod 13:21; 19:16; 20:21; Deut 5:22; I Kings 8:10; and Sir 45:4.

15

J. A. Emerton, "The Origin of the Son of Man Imagery," Journal of Theological Studies 9 (1958): 231-32.

16

Matthew Black, "The Throne—Theophany, Prophetic Commission, and the 'Son of Man,' " in Jews, Greeks, and Christians: Religious Cultures in Late Antiquity: Essays in Honor of William David Davies, ed. Robert G. Hamerton—Kelley and Robin Scroggs (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1976), 61.

17

For a study of the ubiquity of this pattern, see Moshe Idel, Ben: Sonship and Jewish Mysticism, Kogod Library of Judaic Studies (London: Continuum, 2007).

18

Frank Moore Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973), 43.

19

Readers of modern Hebrew will surely find Yisra'el Knohl, Me—Ayin Banu: Ha—Tsofen Ha—Geneti Shel Ha—Tanakh [The Genetic Code of the Bible] (Or Yehudah: Devir, 2008), 102-13, of interest here. Especially riveting is Knohl's idea that YHVH was represented by a golden calf insofar as he was understood as the son of El, who was a bull.

20

After the rabbis, I have found only Sigmund Olaf Plytt Mowinckel, He That Cometh: The Messiah Concept in the Old Testament and Later Judaism, trans. G. W. Anderson (Oxford: B. Blackwell, 1956), 352, emphasizing this point sufficiently, but, of course, since the literature is massive, I may (almost certainly have) missed others.

21

Following the argument made originally by Emerton, "Origin."

22

John J. Collins, Daniel: A Commentary on the Book of Daniel, Hermeneia (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993), 291.

23

I have modified Collins's original list of such patterns in two ways. I have dropped the comparison with the sea, since I believe that the sea vision and the Son of Man vision were once two separate elements, and I have emphasized the differential ages of the two divine figures, which seems to me crucial for understanding the pattern of relationships here.

24

Carsten Colpe, "Ho Huios Tou Anthropou," in Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, vol. 8 (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1972), 8:400-477.

25

Ronald Hendel, "The Exodus in Biblical Memory," in Remembering Abraham (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 57-75.

26

Cross, Canaanite, 58. See also David Biale, "The God with Breasts: El Shaddai in the Bible," History of Religions 21, no. 3 (February 1982): 240-56, and Mark S. Smith, The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel, 2>nd ed. with a foreword by Patrick D. Miller, Biblical Resources Series (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2002), 184.

27

This explanation of Bacal and YHVH as rivals for the young God spot might be taken to explain better the extreme rivalry between them manifested in the Bible

28

Smith, Early History of God, 32-33. Cross, in contrast, had argued that YHVH was originally a cultic name for 'El used in the south; YHVH eventually splits off from and then ousts 3E1 (Cross, Canaanite, 71).

29

A similar explanation, mutatis mutandis, might, just might, help to understand the place of JJokhma, Lady Wisdom, as a virtual consort to God in Proverbs 8 and her connections with Ashera, for which see Smith, Early History of God, 133.

30

It is here that I part company most decisively with Otto Eissfeldt, "El and Yahweh," Journal of Semitic Studies 1 (1956): 2 5 - 37, and Margaret Barker, The Great Angel: A Study of Israel's Second God (London: SPCK, 1992).

31

Daniel Abrams, "The Boundaries of Divine Ontology: The Inclusion and Exclusion of Metatron in the Godhead," Harvard Theological Review 87, no. 3 (July 1994): 291-321.

32

Pace Barker, Great Angel, 40. I thus agree with Emerton's conclusion that "the language used of the Son of man suggests

Yahwe, not the Davidic king." Emerton, "The Origin/' 231.

33

Seen in this light, it really is a sort of quibble to distinguish between second divinity and highest angel. We need to remember that in antiquity monotheism meant not the sole existence of only one divine being but the absolute supremacy of one to whom all others are subordinate (and this was good Christian theology until Nicaea as well). Fredriksen, "Mandatory Retirement," 35-38, is a concise, excellent presentation of this position.

34

"Yahoel" appears in the Apocalypse of Abraham (A. D. 70-150), but then as late as 3 Enoch (fourth–fifth centuries), we find "Little Yahu," "Yahoel Yah," and "Yahoel" explicitly given as names for Metatron. Andrei Orlov, "Praxis of the Voice: The Divine Name Traditions in the Apocalypse of Abraham," Journal of Biblical Literature 127 (2008): 53-70, and Philip S. Alexander, "The Historical Setting of the Hebrew Book of Enoch," Journal of Jewish Studies 28 (1977): 163-64.

35

Collins, Daniel, 281. Collins seems to consider the pattern of religion enshrined in the throne vision as a frozen relic from Israel's past (or even a foreign past): "it has been argued that motifs should not be 'torn out of their living contexts' but 'should be considered against the totality of the phenomenological conception of the works in which such correspondences occur.' Such demands are justified when the intention is to compare the 'patterns of religion' in a myth and a biblical text, but this has never been the issue in the discussion of Daniel 7."

36

See Daniel Boyarin, "Beyond Judaisms: Metatron and the Divine Polymorphy of Ancient Judaism," Journal for the Study of Judaism in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman Periods 41 (July 2010): 323-65.

37

Andrew Chester, "High Christology—Whence, When and Why?" Early Christianity 2, no. 1 (2011): 22-50.

38

Given the meaning of the underlying Aramaic word in Daniel, "authority" strikes me as a rather weak rendering; "sovereignty" would be much better. Sovereignty would surely explain why the Son of Man has the power to remit sins on earth.

39

Cf. Morna Hooker, The Son of Man in Mark: A Study of the Background of the Term "Son of Man" and Its Use in St Mark's Gospel (Montreal: McGill University Press, 1967), 9 0 - 9 1 , who seems to take this (in partial contradiction to her own position earlier) to be significant of a prerogative of "man" in general.

40

As New Testament scholar F. W. Beare has written, "In the gentile churches, this will not have been a burning question in itself; it will have arisen only as one aspect of the much broader issue of how far the Law of Moses was held to be binding upon Christians. Insofar as the pericope [discrete passage of the narrative] is a community–product, accordingly, it will be regarded as a product of Palestinian Jewish Christianity, not of the Hellenistic churches. The way to understanding will therefore lie through the examination of Jewish traditions and modes of thought." F. W. Beare, " The Sabbath Was Made for Man?' " Journal of Biblical Literature 79, no. 2 (June 1960): 130.

41

Generally, and this is highly important, New Testament critics have seen w. 27-28 as an addition to an original text that incorporated only the answer regarding David–or the opposite, that only w. 2 7 - 2 8 were original and that the reference to David is a secondary addition. "As Guelich observes (similarly Back, Jesus of Nazareth, 69; Doering, Schabbat, 409), these four suggestions basically boil down to two: (1) either Jesus' argument from the action of David is original, with w. 27-28 being added later in one or two stages, or (2) v. 27 (and possibly v. 28) constituted Jesus' original answer(s), with the story of David being added later." John Paul Meier, "The Historical Jesus and the Plucking of the Grain on the Sabbath," Catholic Biblical Quarterly 66 (2004): 564.

42

Menahem Kister, "Plucking on the Sabbath and the Jewish- Christian Controversy" [Hebrew], Jerusalem Studies in Jewish Thought 3, no. 3 (1984): 349-66. See also Shemesh, "Shabbat."

43

John P. Meier has written, "Clearly, then, this Galilean cycle of dispute stories is an intricate piece of literary art and artifice, written by a Christian theologian to advance his overall vision of Jesus as the hidden yet authoritative Messiah, Son of Man, and Son of God. As we begin to examine the fourth of the five stories, the plucking of the grain on the Sabbath, the last thing we should do is treat it like a videotaped replay of a debate among various Palestinian Jews in the year A. D. 28. It is, first of all, a Christian composition promoting Christian theology. To what extent it may also preserve memories of an actual clash between the historical Jesus and Pharisees can be discerned only by analyzing the Christian text we have before us." Meier,"Plucking," 567.1

44

Cf. the similar but also subtly different conclusion of Collins, Mark: A Commentary, 205. For me, it is not so much the Messiah as king that is at issue but rather the Son of Man as carrier of divinity and divine authority on earth.

45

This interpretation obviates the apparent non sequitur between w. 27 and 28, pointed to inter alia by Beare," The Sabbath Was Made for Man?' " 130.

46

Cf. Robert H. Gundry, Mark: A Commentary on His Apology for the Cross (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2004 [1993]), I: 144. For other authors holding this view, see discussion in Neirynck, "Jesus and the Sabbath," 2 3 7 - 3 8 , and notes there.

47

As far as I can tell, my view is closest in certain respects to that of Eduard Schweizer, Das Evangelium Nach Markus [Bible. 4, N T Mark. Commentaries], Das Neue Testament Deutsch (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1973), 39-40.

48

For discussion of these two apparent difficulties, see Marcus, Mark 1-8, 243-47.

49

Cf. Beare," The Sabbath Was Made for Man?'" 134.1 disagree with Beare, however, in his assumption that the David argument could only have been mobilized with messianic overtones, given that we find it in rabbinic literature without such overtones and in a very similar context, namely, as a justification for violating the Torah in a situation in which there is a threat to life (even a very mild such threat, such as a sore throat). Palestinian Talmud Yoma 8:6,45:b.

50

For a similar view, see Collins, Mark: A Commentary, 185 n28.

51

Richard Bauckham, "The Throne of God and the Worship of Jesus," in The Jewish Roots of Christohgical Monotheism: Papers from the St. Andrews Conference on the Historical Origins of the Worship of Jesus, ed. Carey C. Newman, Supplements to the Journal for the Study of Judaism (Boston: Brill, 1999), 53. See too Charles A. Gieschen, Angelomorphic Christology: Antecedents and Early Evidence, Arbeiten Zur Geschichte Des Antiken Judentums und Des Urchristentums (Leiden: Brill, 1998), 93-94

52

For the formerly held position that the parables were earlier than this, see Matthew Black, "The Eschatology of the Similitudes of Enoch," Journal of Theological Studies 3 (1953): 1. For the latest and generally accepted position, see essays in Gabriele Boccaccini, ed., Jason von Ehrenkrook, assoc. ed., Enoch and the Messiah Son of Man: Revisiting the Book of Parables (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2007), 415-98, especially David Suter, "Enoch in Sheol: Updating the Dating of the Parables of Enoch," 415-33

53

The major exegetical work to demonstrate that this chapter is constructed as a midrash on Daniel 7:13-14 has been done by Lars Hartman, who shows carefully how many biblical verses and echoes there are in the chapter. Lars Hartman, Prophecy Interrupted: The Formation of Some Jewish Apocalyptic Texts and of the Eschatological Discourse Mark 13, Conjectanea Biblica (Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell, 1966), 118-26. My discussion in this and the next paragraph draws on his, so I will forgo a series of specific references. In any case, I can only summarize his detailed and impressive argument

54

Pierluigi Piovanelli," 'A Testimony for the Kings and Mighty Who Possess the Earth': The Thirst for Justice and Peace in the Parables of Enoch," in Enoch and the Messiah Son of Man: Revisiting the Book of Parables, ed. Gabriele Boccaccini (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2007).

55

James R. Davila, "Of Methodology, Monotheism and Metatron," in The Jewish Roots of Christological Monotheism: Papers from the St. Andrews Conference on the Historical Origins of the Worship of Jesus, ed. Carey C. Newman, Supplements to the Journal for the Study of Judaism (Leiden: Brill, 1999), 9.

56

Moshe Idel, Ben: Sonship and Jewish Mysticism, Kogod Library of Judaic Studies (London: Continuum, 2007), 4.

57

For a study of the ubiquity of this pattern, see Idel, Ben, 1-3.

58

Adela Yarbro Collins, Mark: A Commentary, ed. Harold W. Attridge, Hermeneia—a Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2007), 356. It should be emphasized that Collins does not consider this necessarily the meaning of Jesus' original pronouncement at v. 15, but she does so read v. 19, which is a gloss by the evangelist Mark, thus rendering Mark (like Paul) the beginning of the end of the Law for Christians.

59

Robert A. Guelich, Mark 1-8:26, Word Biblical Commentary 34A; Mark; I-VIII (Dallas, TX: Word Books, 1989), 380.

60

See too for instance, "Mark, our earliest gospel, offers a more reliable standard [than Paul]; and it says that Jesus abrogated laws of food and purity and violated the Sabbath"; Robert H. Gundry, Mark: A Commentary on His Apology for the Cross(Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1993, 2004). This may be "a known fact" for Gundry; hardly for me.

61

Following Martin Goodman, who writes, "Jesus (or Matthew) was attacking Pharisees for their eagerness in trying to persuade other Jews to follow Pharisaic halakah"; Martin Goodman, Mission and Conversion: Proselytizing in the Religious History of the Roman Empire (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994), 70. This is surely not the only possible interpretation, but it is the one that makes the most sense to me.

62

To be sure, the confusion has been partly engendered by the biblical usage itself. There is one area in which the terminology is muddled. Of the animals that we may eat and may not eat, the Torah uses the terms "pure" and "impure." Nonetheless, the distinction between the two systems–what makes foods kosher or not and what makes kosher foods impure or not–remains quite clear despite this terminological glitch. In the later tradition, only the word "kosher" is used for the first, while "pure" means only undefiled.

63

Marcus, Mark 1-8, 439, but on 441 he is still doubtful. I, of course, agree with the translation, disagree with the doubt.

64

The hermeneutic logic here is similar to that of Marcus in remark 2:23 (Marcus, Mark 1-8, 239) where the emphasis on"making a way" is taken as an allusion to the way that Jesus is making in the wilderness (the field). I am suggesting that Mark's emphasis on "with a fist," which is in itself quite realistic but seemingly trivial, has a similar symbolic overtone.

65

Yair Furstenberg, "Defilement Penetrating the Body: A New Understanding of Contamination in Mark 7.15," New Testament Studies 54 (2008): 178.

66

Tomson, 81, has brought this text to bear on Mark 7. It should be further pointed out, according to the Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 14a, that Rabbi Eliezer holds an even stricter standard than this; it is still within the category of rabbinic (Pharisaic) innovation or the "traditions of the Elders," just as Jesus dubs it.

67

Collins, Mark: A Commentary, 350. Given, however, that she so precisely articulates this, I cannot understand how on the next page she approves of Claude Montefiore's statement that "the argument in w. 6-8 is not compelling." It is as compelling as can be as described above: "Why, Pharisees, are you setting aside the commandments of God in favor of the commandments of humans–handwashings, vows–as the Prophet prophesied?"

68

In chapter 2, there is also a passage that is, I think, illuminated by such a perspective. In w. 18-22, some people wonder why other pietists (the disciples of John and the Pharisees) engage in fasting practices, while the disciples of Jesus do not. Jesus answers that they may not fast in the presence of the bridegroom, which is clearly a halakhic statement interpreted spiritually to refer to the holy, divine Bridegroom of Israel. As Yarbro Collins makes clear, this is another indirect claim on Jesus' part to be divine {Mark: A Commentary, 199).

69

Albert I. Baumgarten, "The Pharisaic Paradosis," HarvardTheobgical Review 80 (1987): 63-77.

70

This is close to the view of Sean Freyne, Galilee, from Alexander the Great to Hadrian, 323 B. C. E. to 135 C. E.: A Study of Second Temple Judaism, University of Notre Dame Center for the Study of Judaism and Christianity in Antiquity, 5 (Wilmington, DE: M. Glazier, 1980), 3 1 6 - 1 8 , 3 2 2.

71

Weston La Barre, The Ghost Dance: Origins of Religion (London:Allen and Unwin, 1972), 254

72

Joseph Klausner, "The Jewish and Christian Messiah/' in TheMessianic Idea in Israel, from Its Beginning to the Completion of the Mishnah, trans. W. F. Stinespring (New York: Macmillan, 1955), 519-31.

73

See Martin Hengel, "The Effective History of Isaiah 53 in the Pre—Christian Period," in The Suffering Servant: Isaiah 53 in Jewish and Christian Sources, ed. Bernd Janowski and Peter Stuhlmacher, trans. Daniel P. Bailey (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2004), 137-45, for good arguments to this effect. Hengel concludes, "The expectation of an eschatological suffering savior figure connected with Isaiah 53 cannot therefore be proven to exist with absolute certainty and in a clearly outlined form in pre-Christian Judaism. Nevertheless, a lot of indices that must be taken seriously in texts of very different provenance suggest that these types of expectations could also have existed at the margins, next to many others. This would then explain how a suffering or dying Messiah surfaces in various forms with the Tannaim of the second century C. E., and why Isaiah 53 is clearly interpreted messianically in the Targum and rabbinic texts" (140). While there are some points in Hengel's statement that require revision, the Targum is more a counterexample than a supporting text, and for the most part he is spot on.

74

Hengel, "Effective History/' 133-37, even makes a case that the Septuagint (Jewish Greek translation) to Isaiah (second century B. C. ) may already have read the Isaiah passage as referring to the Messiah.

75

While it is universally acknowledged that w. 14:61-64 are an unambiguous allusion to Daniel 7:13, scholars who cannot abide the idea that Jesus himself claimed messianic status or to be the Son of Man have either denied that these could have been Jesus' true words (Lindars) or understood them as Jesus speaking about someone else (Bultmann) (and see 13:25 as well). The clear sense of these words, however, as written by Mark in his Gospel is that here Jesus speaks of himself.

76

I do not know early evidence outside of the Gospels for this particular way of reading the Daniel material as applying to a suffering Messiah, still less to a dying and rising one, and I have no reason to think that it did not fall into place in this particular Jewish Messianic movement. (As we shall see below, however, the reading of this as referring to the Messiah is not unknown to later rabbinic Judaism, not at all.) It should be noted that also in Fourth Ezra, discussed above in chapter 2, an enemy arises to the Messiah, an enemy eventually defeated by him forever and ever

77

This punctuation is Wellhausen's, as reported in Joel Marcus, The Way of the Lord: Christological Exegesis of the Old Testament in the Gospel of Mark (Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1992), 99.

78

Marcus's great insight was that the Gospel text thematizes the contradiction. He somewhat goes off track in the beginning of his discussion by citing (in the way of Dahl) the tannaitic rule of "two verses that contradict each other"; the correct comparison is to the midrashic form of the Mekhilta, which is given later. This initial confusion has some consequences, for which see below.

79

From here on, I will be following Marcus quite closely. Marcus, Way of the Lord, 106

80

It should be noted that in some respects the Matthean parallel goes in quite a different direction from Mark, especially by leaving out the crucial "It is written" statements in both instances. There is no midrash in Matthew here at all. For other entailed differences in this passage between the second and the first Gospels, see W. D. Davies and Dale C. Allison Jr., A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to Saint Matthew, International Critical Commentary (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1988), 712. If Marcus and I are right, then Mark is much closer to a Jewish hermeneutical form than Matthew at this point.

81

Origen, Contra Cekum, trans, with an introduction and notes by Henry Chadwick (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965), 50.

82

The word for "disease" here means "leprosy" throughout rabbinic literature and is translated leprosus by Jerome as well (for the latter reference, see Adolph Neubauer, The Fifty—Third Chapter of Isaiah According to the Jewish Interpreters (Oxford: J. Parker, 1876-1877), 6.

83

I am not claiming that therefore the followers of Jesus did not originate this particular midrash, rather, if and when they did so, the hermeneutical practice they were engaged in bespoke in itself the "Jewishness" of their religious thinking and imagination.

84

Martin Hengel, "Christianity as a Jewish—Messianic Movement," in The Beginnings of Christianity: A Collection of Articles, ed. Jack Pastor and Menachem Mor (Jerusalem: Yad Ben—Zvi Press, 2005), 85, emphasis in original.

В этом томе подробно излагается вероучение адвентистов седьмого дня и дается его детальное разъяснение на основании глубокого и всестороннего анализа библейского текста и новейших исследований в области систематического богословия.

В этой книге популярно и увлекательно рассказывается о зарождении, расцвете и крушении загадочной цивилизации майя. Вы узнаете о народе, который строил прекрасные города-государства и замечательно вел сельское хозяйство. В его религии огромную роль играла астрология и, благодаря этому обстоятельству, совершенствовались математика и астрономия. Майя смогли создать точнейшие календари, поразительную архитектуру и искусство, проникнутые их глубокими и таинственными верованиями.

В своей книге известный советский историк-религиовед Ефим Фёдорович Грекулов, основываясь исключительно на подлинных источниках, предлагает вниманию читателя несколько очерков, посвященных истории русского духовенства. Эти очерки, знакомя читателя с различными скрытыми бытовыми особенностями духовенства, являются достаточно показательными для обстоятельной оценки этого явления российской истории.Книга представляет интерес для самых широких читательских кругов.

Невероятный успех Дэна Брауна и его последователей в очередной раз показал огромную популярность христианской темы. Но книг, посвященных «новым прочтениям» и «тайнам» христианства, издано гораздо больше, чем книг о собственно христианстве, особенно написанных для нецерковной аудитории. Именно этим объясняется «экскурс» Елены Прудниковой, автора нашумевших исторических исследований, посвященных сталинской эпохе, в такую, казалось бы, неожиданную область.Возможно ли соединить приверженность Православию с исторической объективностью? Традиционно «скучную» религиозную тему с основным принципом автора «книга должна быть интересной»? Оказалось, возможно – и не только это.

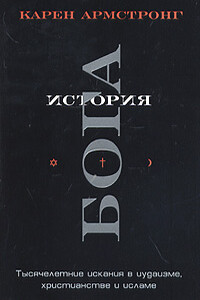

Откуда в нашем восприятии появилась сама идея единого Бога?Как менялись представления человека о Боге?Какими чертами наделили Его три мировые религии единобожия — иудаизм, христианство и ислам?Какое влияние оказали эти три религии друг на друга?Известный историк религии, англичанка Карен Армстронг наделена редкостными достоинствами: завидной ученостью и блистательным даром говорить просто о сложном. Она сотворила настоящее чудо, охватив в одной книге всю историю единобожия — от Авраама до наших дней, от античной философии, средневекового мистицизма, духовных исканий Возрождения и Реформации вплоть до скептицизма современной эпохи.

В книге рассказывается история главного героя, который сталкивается с различными проблемами и препятствиями на протяжении всего своего путешествия. По пути он встречает множество второстепенных персонажей, которые играют важные роли в истории. Благодаря опыту главного героя книга исследует такие темы, как любовь, потеря, надежда и стойкость. По мере того, как главный герой преодолевает свои трудности, он усваивает ценные уроки жизни и растет как личность.