36 Arguments for the Existence of God - [62]

“You don’t have?” It was the little boy who spoke.

“No, I don’t. It was just me when I was growing up.”

“Were you sad?” The child’s voice was high and chimelike.

Again the older sister felt compelled to issue a gentle “shah.”

“No, I don’t think so. I had lots of friends. And my parents were my friends, too. They were my playmates!”

All four of the children stared at her with concentrated seriousness, even the youngest, as if they were trying to interpret her words. Perhaps their English wasn’t very good.

Roz was not sentimental when it came to children. She found the standardized cuteness of kids about as inspiring as the standardized intelligence of grown-ups. She’d never been the kind of girl who spent much time with kids. She hadn’t babysat, and she hadn’t taken summer jobs as a camp counselor. Children had always left her cold until she studied the Onuma kids as part of her field research. She found most of them to be pains in the neck, though she’d grown fond of a few of them, particularly one, whom she had nicknamed Tsetse, and who was such a creative liar that even the elders admired him.

“Still, I think it must be lovely to be four like the four of you.”

“We have more,” said the little boy.

This time the older sister gave her brother a warning look that needed no interpretation.

Just then, a tall, thin woman came into the room. She was in a dun-colored dress and thick flesh-colored stockings, and the same clunky style of shoes as the girls. She was wearing a matching dun-colored wig. Her face lit up when she saw the children. Actually, it was the little boy she directed her glow to, and she cooed at him in Yiddish, apparently telling him to come to her.

He got up and walked over to her, and she took his hand and brought it to her lips lovingly. Was this the mother? She didn’t look like the children, certainly not like the enchanting little boy. And she didn’t spare a glance for the girls.

She asked the little boy something, and he answered “Ya” and turned back to Roz.

“I have to go now. I’m going to see my tata,” he said to her. She surmised that this meant “daddy.”

“Is your tata the Rebbe?” she asked.

The children, even the little boy, looked down at the floor in response, and the dun-colored woman sharply asked Roz, whom she hadn’t deigned to notice before, “Who you?”

“I’m here to see the Rebbe.” Roz extravagantly rolled the r of “Rebbe,” which was both fun and, she thought, helpful in convincing them of her respectful attitude. “I had an appointment to see him at four o’clock. I drove in from Boston with my two friends.”

“Yes, they’re mit da Rebbe now. If you want, come.”

Holding the little boy’s hand-the sisters were left behind, never glanced at-the woman led the way down a corridor into a little antechamber, where she knocked at a door. A bearded man poked his head out, took a look at the boy, and opened the door for him. Roz slipped in behind the child. The man quickly looked at her sideways and then closed the door behind her.

They were in a book-lined study, with a large desk behind which was sitting a pudgy man in a shiny black coat and a beard in the white, flowing model they stick on soldiers of the Salvation Army around Christmastime, and one superlative fur hat. There were two full-bearded subordinates standing guard behind him, and seated in front of the desk, cozy as could be, were Cass and Klapper. The seated man in the headdress could only be the tribal chief, and, judging by his circumference, the choicest matzo balls went to him. (The Valdeners, from what Roz had seen of them, were a pale, malnourished lot.) The Rebbe took no notice of Roz’s entrance-nobody did-but he smiled broadly when he saw the boy, and he gestured for him to come. The boy went straight over to the chief-perhaps tata meant “grandpa” rather than “papa”-and was lifted up onto the ample royal lap.

“My son,” he said to Cass and Klapper. “Your sisters brought you, tateleh?”

“Ya, Tata.”

“How many sisters do you have, tateleh?” Roz asked, even though it had been impressed on her that the rules of female modesty required her to render herself as close to nonexistent as possible.

The boy stared at her, wide-eyed. It wasn’t the endearment that had startled him: it was her question.

“Don’t you know, sweetie? Don’t you know how to count?”

“He knows to count,” the Rebbe said forcefully, “Believe me, miss, that he knows how to do!”

Klapper turned back to where Roz was standing against the wall, gave her a glance, and then turned back.

“There is an ancient prohibition against the counting of people, which we learn from the account of the sin of King David recorded in both Samuel and 1 Chronicles. King David ordered his lieutenants to count the men of fighting age and displeased God with his action, and God began to smite Israel. David repented of his sin and asked for God’s forgiveness and was given his choice of punishments, either three years of famine, three months of being vanquished by enemies, or three days of ‘the sword of the Lord,’ which would consist of a deadly plague that would sweep through the land. David chose the latter, and a great many of Israel fell dead.”

Сначала мы живем. Затем мы умираем. А что потом, неужели все по новой? А что, если у нас не одна попытка прожить жизнь, а десять тысяч? Десять тысяч попыток, чтобы понять, как же на самом деле жить правильно, постичь мудрость и стать совершенством. У Майло уже было 9995 шансов, и осталось всего пять, чтобы заслужить свое место в бесконечности вселенной. Но все, чего хочет Майло, – навсегда упасть в объятия Смерти (соблазнительной и длинноволосой). Или Сюзи, как он ее называет. Представляете, Смерть является причиной для жизни? И у Майло получится добиться своего, если он разгадает великую космическую головоломку.

В книге рассказывается история главного героя, который сталкивается с различными проблемами и препятствиями на протяжении всего своего путешествия. По пути он встречает множество второстепенных персонажей, которые играют важные роли в истории. Благодаря опыту главного героя книга исследует такие темы, как любовь, потеря, надежда и стойкость. По мере того, как главный герой преодолевает свои трудности, он усваивает ценные уроки жизни и растет как личность.

Настоящая книга целиком посвящена будням современной венгерской Народной армии. В романе «Особенный год» автор рассказывает о событиях одного года из жизни стрелковой роты, повествует о том, как формируются характеры солдат, как складывается коллектив. Повседневный ратный труд небольшого, но сплоченного воинского коллектива предстает перед читателем нелегким, но важным и полезным. И. Уйвари, сам опытный офицер-воспитатель, со знанием дела пишет о жизни и службе венгерских воинов, показывает суровую романтику армейских будней. Книга рассчитана на широкий круг читателей.

Боги катаются на лыжах, пришельцы работают в бизнес-центрах, а люди ищут потерянный рай — в офисах, похожих на пещеры с сокровищами, в космосе или просто в своих снах. В мире рассказов Саши Щипина правду сложно отделить от вымысла, но сказочные декорации часто скрывают за собой печальную реальность. Герои Щипина продолжают верить в чудо — пусть даже в собственных глазах они выглядят полными идиотами.

Роман «Деревянные волки» — произведение, которое сработано на стыке реализма и мистики. Но все же, оно настолько заземлено тонкостями реальных событий, что без особого труда можно поверить в существование невидимого волка, от имени которого происходит повествование, который «охраняет» главного героя, передвигаясь за ним во времени и пространстве. Этот особый взгляд с неопределенной точки придает обыденным события (рождение, любовь, смерть) необъяснимый колорит — и уже не удивляют рассказы о том, что после смерти мы некоторое время можем видеть себя со стороны и очень многое понимать совсем по-другому.

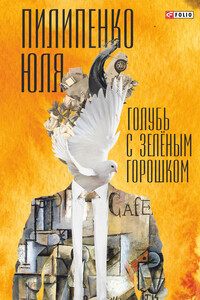

«Голубь с зеленым горошком» — это роман, сочетающий в себе разнообразие жанров. Любовь и приключения, история и искусство, Париж и великолепная Мадейра. Одна случайно забытая в женевском аэропорту книга, которая объединит две совершенно разные жизни……Май 2010 года. Раннее утро. Музей современного искусства, Париж. Заспанная охрана в недоумении смотрит на стену, на которой покоятся пять пустых рам. В этот момент по бульвару Сен-Жермен спокойно идет человек с картиной Пабло Пикассо под курткой. У него свой четкий план, но судьба внесет свои коррективы.