36 Arguments for the Existence of God - [46]

“The borderlands between Brazil and Venezuela. I’m mostly in Venezuela. I lived in a village called Meesa-teri. Teri just means ‘village.’”

“Do you speak… what’s the language they speak?”

“They speak Onuma. That’s what we call it. They don’t have a name for themselves. ‘Onuma’ is a name from the Kentubas, another tribe, and it means ‘dirty feet.’ Is this the reception for Klapper?” she asked a woman inside the Faculty Club who was sitting behind a table.

“Yes, it is.” She smiled in a transparently perfunctory way. “Your name, please?”

The girl turned to Cass with a flourish, gesturing for him to go first.

“Um, yes, I’m Cass Seltzer.”

“I have it, Cass,” the woman said, her traveling finger stopping at a name on her list. She handed him a name tag. “And your name, miss?”

“I’m with him,” the girl said.

“I still need your name.” The perfunctory smile was growing rigid round the corners. The woman had an upper lip so stiff it looked as if it could make puncture wounds.

“Roslyn Margolis.”

“I don’t seem to have you on the list, Ms. Margolis.”

“Are you sure? Didn’t you inform them I was coming, Cass?”

“I don’t know.”

Roslyn Margolis smiled at the gatekeeper.

“Absentminded professors!”

“Oh, are you a professor, Professor Cass, I mean, Professor Seltzer? Excuse me. I hadn’t realized. You look so young.”

“He is young! He’s a prodigy! That’s why he’s so absentminded! Cass, how could you have forgotten to let the club know I was coming with you?”

“Oh well, not to worry. This can be remedied lickety-split,” said the gatekeeper, producing a magic marker and the fixings for a name tag. “You know,” she said to Roslyn in a confidential tone, “we have quite a few professors who forget to mention their significant others.”

“Oh, thanks. I appreciate it. We could have used your help the last time this happened. I was almost kept out of seeing him inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences,” said Roslyn Margolis, pinning on her name tag.

“Oh my! The Academy! And so young! Well, wonderful to have met you both!”

Cass stared at Roslyn Margolis. He had begun to doubt everything she had said up until this moment, not excluding that her name was Roslyn Margolis.

“Anyway,” the girl continued, as they headed into the reception area, “so far as my speaking Onuma, I do speak some. There are lots of dialects. Sometimes people from one village can’t understand the people from another village. They can be pretty isolated from each other. There are still lots of villages that haven’t had any contact with outsiders.”

“Are they noble savages?”

“Noble savages?”

“You know, uncorrupted by society’s venality.”

“Frolicking like bunnies in Rousseau’s Never-Never Land? Funny you should ask. When I first applied to be Absalom’s student-he was wary of me, since I was coming from studying the kind of anthropology he doesn’t have much use for, but, then, I didn’t either, so it worked out great-but when I first met him, I asked him what they were really like, the Onuma, and he said, ‘They’re assholes.’”

She laughed. She had a wonderfully lusty laugh. Cass couldn’t hear it without grinning himself.

“And are they?”

“Assholes? It’s against the anthropologist religion to say anything judgmental, so if it strikes you as judgmental then don’t repeat it, or Absalom or I will have to kill you, which we’re capable of, but, yeah, basically they’re assholes. They’re not noble-savage pretty. The Onuma are about as good a counterexample as you’re going to find for a universal moral instinct. They don’t seem to have any compunctions about lying or stealing, the men can beat their wives whenever they feel the need to, they’re constantly raiding each other’s women, which is how their wars start, it’s always about kidnapping women, and then the raided go raiding to get them back, preferably taking a few extra women with them as long as they’re going to the trouble, and they have an unquenchable thirst for revenge.”

“It sounds like a dangerous place to be a woman.”

“It’s a dangerous place to be a human.”

“And what do they make of you?”

Roslyn Margolis, if that was indeed her name, was a tall, slender girl, only a few inches shorter than Cass, but she looked, despite her slenderness, as if she would never have to ask a man to remove any twist-off top for her. Her face looked strong, too. There was something bold and arresting. Once you really looked at her, it was hard to look away. She had a high-bridged nose and clear blue eyes, and her upper lip looked sweetened by all the laughter it had laughed, it looked generous to share that laughter with others, and it looked, despite all its fun, noble. Her whole bearing had something noble about it. But, even with the height and obvious physical strength and the suggestion of nobility, she was feminine.

She was certainly dressed feminine, in a long peacock-blue skirt of crinkly velvet and a silky blouse in the same color that was shot through with gold embroidery. She was one of those women that could qualify as beautiful without being pretty. It was something about the sheer quantity of life that seemed compressed into her.

Я был примерным студентом, хорошим парнем из благополучной московской семьи. Плыл по течению в надежде на счастливое будущее, пока в один миг все не перевернулось с ног на голову. На пути к счастью мне пришлось отказаться от привычных взглядов и забыть давно вбитые в голову правила. Ведь, как известно, настоящее чувство не может быть загнано в рамки. Но, начав жить не по общепринятым нормам, я понял, как судьба поступает с теми, кто позволил себе стать свободным. Моя история о Москве, о любви, об искусстве и немного обо всех нас.

Сергей Носов – прозаик, драматург, автор шести романов, нескольких книг рассказов и эссе, а также оригинальных работ по психологии памятников; лауреат премии «Национальный бестселлер» (за роман «Фигурные скобки») и финалист «Большой книги» («Франсуаза, или Путь к леднику»). Новая книга «Построение квадрата на шестом уроке» приглашает взглянуть на нашу жизнь с четырех неожиданных сторон и узнать, почему опасно ночевать на комаровской даче Ахматовой, где купался Керенский, что происходит в голове шестиклассника Ромы и зачем автор этой книги залез на Александровскую колонну…

Сергей Иванов – украинский журналист и блогер. Родился в 1976 году в городе Зимогорье Луганской области. Закончил юридический факультет. С 1998-го по 2008 г. работал в прокуратуре. Как пишет сам Сергей, больше всего в жизни он ненавидит государство и идиотов, хотя зарабатывает на жизнь, ежедневно взаимодействуя и с тем, и с другим. Широкую известность получил в период Майдана и во время так называемой «русской весны», в присущем ему стиле описывая в своем блоге события, приведшие к оккупации Донбасса. Летом 2014-го переехал в Киев, где проживает до сих пор. Тексты, которые вошли в этот сборник, были написаны в период с 2011-го по 2014 г.

В городе появляется новое лицо: загадочный белый человек. Пейл Арсин — альбинос. Люди относятся к нему настороженно. Его появление совпадает с убийством девочки. В Приюте уже много лет не происходило ничего подобного, и Пейлу нужно убедить целый город, что цвет волос и кожи не делает человека преступником. Роман «Белый человек» — история о толерантности, отношении к меньшинствам и социальной справедливости. Категорически не рекомендуется впечатлительным читателям и любителям счастливых финалов.

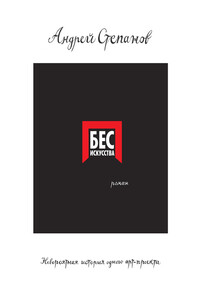

Кто продал искромсанный холст за три миллиона фунтов? Кто использовал мертвых зайцев и живых койотов в качестве материала для своих перформансов? Кто нарушил покой жителей уральского города, устроив у них под окнами новую культурную столицу России? Не знаете? Послушайте, да вы вообще ничего не знаете о современном искусстве! Эта книга даст вам возможность ликвидировать столь досадный пробел. Титанические аферы, шизофренические проекты, картины ада, а также блестящая лекция о том, куда же за сто лет приплыл пароход современности, – в сатирической дьяволиаде, написанной очень серьезным профессором-филологом. А началось все с того, что ясным мартовским утром 2009 года в тихий город Прыжовск прибыл голубоглазый галерист Кондрат Евсеевич Синькин, а за ним потянулись и лучшие силы актуального искусства.